The First Rule of Co-Parenting after Divorce: Put the Child First

In the previous post in this series, we wrote about how co-parenting doesn’t actually reduce the need for communication — it raises the stakes on it. Divorce can end a marriage, but it doesn’t end responsibility. If anything, it demands more intention, more clarity, and more emotional regulation than before.

This post is about the foundational shift that made everything else possible for us.

We’re calling it Rule #1: The Child’s Needs Comes First

This rule didn’t mean our child got everything he wanted. It didn’t mean permissive parenting or avoiding hard boundaries. It meant that decisions were filtered through one question, again and again:

What actually serves this child’s long-term well-being?

When that question is the anchor, a lot of ego-driven power struggles fall away.

Being on the Same Side

One of the biggest misconceptions about divorce is that it’s a release from conflict and conversation. And yes, sometimes it is a release from a romantic relationship that wasn’t working. But if you share a child, it is not a release from responsibility.

What made co-parenting work for us was a simple but relentless reorientation:

We were never on opposite sides.

We were always on our child’s side.

If your ego, hurt, fear, or resentment is driving a decision, pause.

You are the adult with coping skills.

Your child is not.

Being on the child’s side doesn’t mean pretending we don’t have feelings. It means knowing where those feelings belong. Hurt, frustration, and grief don’t magically disappear. But they go off to the side. Not erased. Not denied. Just not driving the bus.

Only then can we consistently return to the key question (it bears repeating):

What actually serves this child’s long-term well-being?

Decades of research on child development and divorce back this up.

Psychologist E. Mavis Hetherington out of UVA, whose longitudinal studies followed children of divorce for over 30 years, found that children do not struggle because their parents divorced. They struggle when they are exposed to chronic parental conflict, emotional triangulation, or forced loyalty.

Similarly, Dr. Joan Kelly, a clinician, mediator, and expert in high conflict divorce, consistently found that the single most protective factor for children is not equal time or identical households, but emotionally regulated parents who can prioritize the child’s needs over their own grievances.

In other words:

Children don’t need parents who agree on everything.

They need parents who can keep their own emotions from becoming the child’s problem.

Ego yells. Regulation whispers.

Rule #1 asks something deceptively simple and profoundly hard:

What would I choose if I weren’t trying to protect myself right now?

If your ego, hurt, fear, or resentment is driving the decision … PAUSE.

You are the adult with coping skills.

Your child is not.

This is especially important when parents hold different values, priorities, or worldviews. Divorce doesn’t freeze people in place. Parents grow, change, and sometimes express deeply held beliefs in very different ways.

What helped us, and what Rebekah sees help many of the families she works with, is learning to separate the goal from the path.

Are you actually disagreeing about the kind of human you hope your child becomes?

Or are you disagreeing about how to get there?

When we slowed down enough to ask that question, we often discovered we were aligned on the outcome, even when our preferred routes looked very different.

One of the clearest moments when this rule was tested for us came during mediation, as we worked to build a long-distance parenting plan across nearly two thousand miles. For Sean, it meant accepting that he wouldn’t see our child every week. For Rebekah, it meant giving up every Thanksgiving, and every joyful summer break.

In Sean’s words: “That wasn’t fair. And it didn’t matter. What mattered was that our son would have stability, continuity in his education, and have two parents who could both make a living.”

The grief of missing daily life and big moments (the skinned knee, the family reunion, the first the bike ride, the lost tooth) belonged to the adult. Holding that loss was part of the job.

We both had to lean into the roles we could play in our child’s life: bringing curiosity about the world, instilling a sense of adventure, guiding him to be responsible for his actions, and showing up with a deep presence even when our time together was limited. It hurt. And it was still the right decision.

That’s what being on the child’s side looks like in real life. Not the absence of pain, but the willingness to carry it without handing it to your child.

Indulging that grief and letting it “take the wheel” would have gotten in the way of keeping the child’s needs first. For some families this looks like fighting over the number of days in the custody agreement, or making the adult’s grievances the topic of every goodbye at the airport. For others, it’s debates over rules and bedtimes, how many sports to play, or when to get their first phone.

Success in those smaller moments comes from finding the strategies that work for you and your personal dynamic. We have found that talking about big decisions (when to get a phone and what the expectations are around it, for example) well ahead of when they come up works for us. It keeps us level-headed and unemotional because we’re talking about something that’s still theoretical, rather than on-demand and emotional. Someday we’ll put all of those strategies together into a workbook for you, but for now, we encourage you to keep slowing down and asking that repeating question: What actually serves this child’s long-term well-being?

There Can’t Be an Enemy

If the child’s needs come first, your co-parent can’t be your enemy.

When lawyers turn co-parenting into a fight, it becomes incredibly hard to recover a shared sense of purpose. In many ways we were lucky, but we were also deliberate. We chose, again and again (sometimes painfully) to put our egos in the backseat. Not every person is going to have a co-parent willing to do the same thing, but each of us can definitely choose that path for ourselves.

That didn’t mean giving up on what mattered. It meant learning discernment. Not every disagreement is a hill worth dying on. Some decisions simply don’t warrant the emotional cost of battle. Your co-parenting relationship will be the capital that matters when those truly impactful decisions need to be made.

In Rebekah’s words: “When R. was 11 there was one point where he pointed out to us that he ‘never got a vacation.’ I was confused because he went out to his dad’s in Colorado all the time over school breaks and had the same amount of time off as all of his friends. But he explained that on breaks he was always transtioning and whichever house he was at his parents were working — what he was really asking for was downtimes. I’m fast-forwarding through a lot of work and conversation, but at the end of the day we were able to shift our schedules a bit and we were able to give Rhyer was able to have some extra days with me on some shorter breaks to just rest and chill. That never would have happened if Sean had dug in his heels about “his time” or if we prioritized custody calculus over the needs of our child. I’m forever grateful for that because we have a much more emotionally healthy child as a result of that decision.”

Rule #1 is not about schedules, parenting apps, or perfectly worded texts. It’s not about custodial time. It’s not about where your child goes to school or how old they are before they get their phone.

Rule #1 is about the internal work.

It’s the moment you don’t send the message.

The space you take before responding to something that activates you.

The willingness to step back and ask, Am I doing this for me? Or for them?

It’s unseen.

It’s unglamorous.

And it’s foundational.

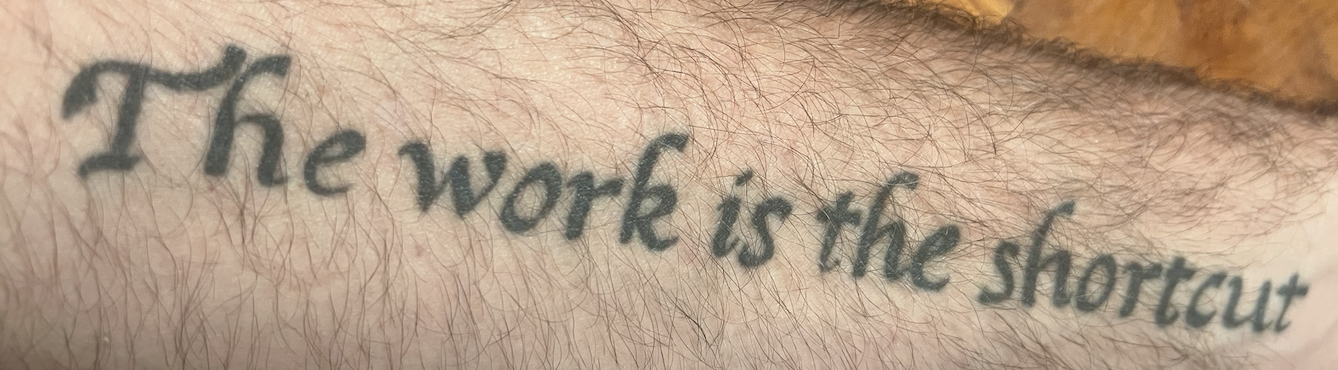

It’s so core that Sean even has it tattooed on his arm:

Because regulation takes work. And regulation is what let’s us separate ego from the needs of our child. We couldn’t have gotten there without spending a lot of time working on ourselves.

In the next post, we’ll build on this foundation and turn toward what happens between co-parents. How communication (not competition) either supports or undermines everything Rule #1 is meant to protect.

This series is grounded not just in lived experience, but in decades of research and reflection on what children actually need when families change. If this post resonated and you want to explore the thinking behind it more deeply, these voices are worth your time:

E. Mavis Hetherington, Ph.D.

A pioneering developmental psychologist whose longitudinal research followed children of divorce for over 30 years. Her work consistently showed that it’s not divorce itself that harms children, but chronic parental conflict and emotional triangulation.

Recommended starting point: For Better or For Worse: Divorce ReconsideredJoan B. Kelly, Ph.D.

One of the most influential researchers on co-parenting after divorce. Kelly’s work focuses on how emotionally regulated, cooperative parenting—rather than rigid schedules or “equal time”—best supports children’s long-term adjustment.

Recommended reading: “Developing Beneficial Parenting Plan Models for Children Following Separation and Divorce” and “Top 10 Ways to Protect your Kids from the Fallout of a High Conflict Break-Up”Daniel J. Siegel, M.D.

Psychiatrist and pioneer of interpersonal neurobiology, Siegel’s work on emotional regulation and brain development helps explain why children can’t and shouldn’t carry an adult emotional load. His research is at the forefront of the idea that regulation has to come before communication.

Recommended starting point: The Whole-Brain ChildPema Chödrön

Buddhist teacher and author whose teachings on staying with discomfort, loosening our grip on certainty, and “getting unstuck” offer practical wisdom for moments when co-parenting becomes emotionally charged. Her work is especially helpful for recognizing when something has become a “hill to die on.”

Recommended starting point: When Things Fall Apart or her talks on “Getting Unstuck”

These voices come from different disciplines: developmental psychology, family systems, law, neuroscience, and spirituality, but they converge on the same truth:

Children do best when adults are willing to do their own internal work first.